The modern day hero wouldn’t be caught wearing a cape, or fighting crime in an iron suit, or seen contemplating life from the tops of skyscrapers.

The modern day heroes are the people who inspire us to strive when the future is grim, to take another step when it seems impossible, to dance like no one is watching (when really, there’s always someone watching). The modern day hero inspires us by being their genuine selves.

As a regular civilian, I search for these kinds of extraordinary people; those that are inspirational in every day life. I yearn for them, I hunger for them: the heroes that save the day, on the daily.

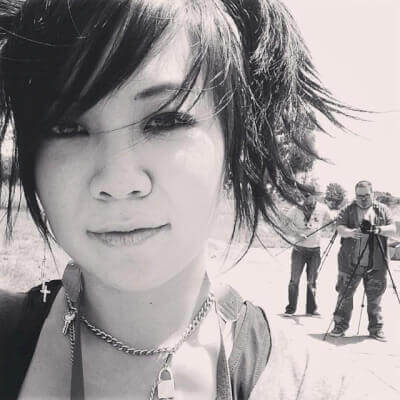

Every February 17th, Lionel Wong gets a new tattoo. Sometimes he decides on the tattoo in a matter of months; sometimes it takes him a year. He doesn't know how much time he's spent under the needle, but he's confident that it's over 30hrs. The tradition began in 2006, when, at age thirty, after a gruelling year of chemotherapy and radiation, Lionel discovered that his lymphoma was in remission.

"For me, design and advertising is artistic. It's no different from singing, dancing, performing. You either have it or you don't. School will help, but if you don't have the skill in you, that's a wrap."

Today, Lionel is a Associate Creative director at HUGE, a global digital agency. He is self-taught and uncompromising, his vocabulary seasoned with expletives and his attitude pulsing with confidence. He never agreed with formal education, explaining, "History, math, english, science - you basically memorize it. I would go through my textbooks again and again, but I'm no good at memorizing shit. I couldn't do it. The only OAC I got was in drama - 95% in drama - but you need six to go to university. That wasn't meant for me. I didn't really know what I wanted to do, because the system I grew up in didn't nurture the arts."

After leaving high school, he took some fundamental courses at a couple of different post secondary institutes and began designing. Drawing from what he had learned in his stint at post-secondary, he built a portfolio, got a lucky break with one agency, and worked his way across Toronto for fifteen years before landing in his current position. "I wrote an article about making a portfolio, and one of the first things I said was, 'I don't give a shit about where you went to school.' For me, design and advertising is artistic. It's no different from singing, dancing, performing. You either have it or you don't. School will help, but if you don't have the skill in you, that's a wrap."

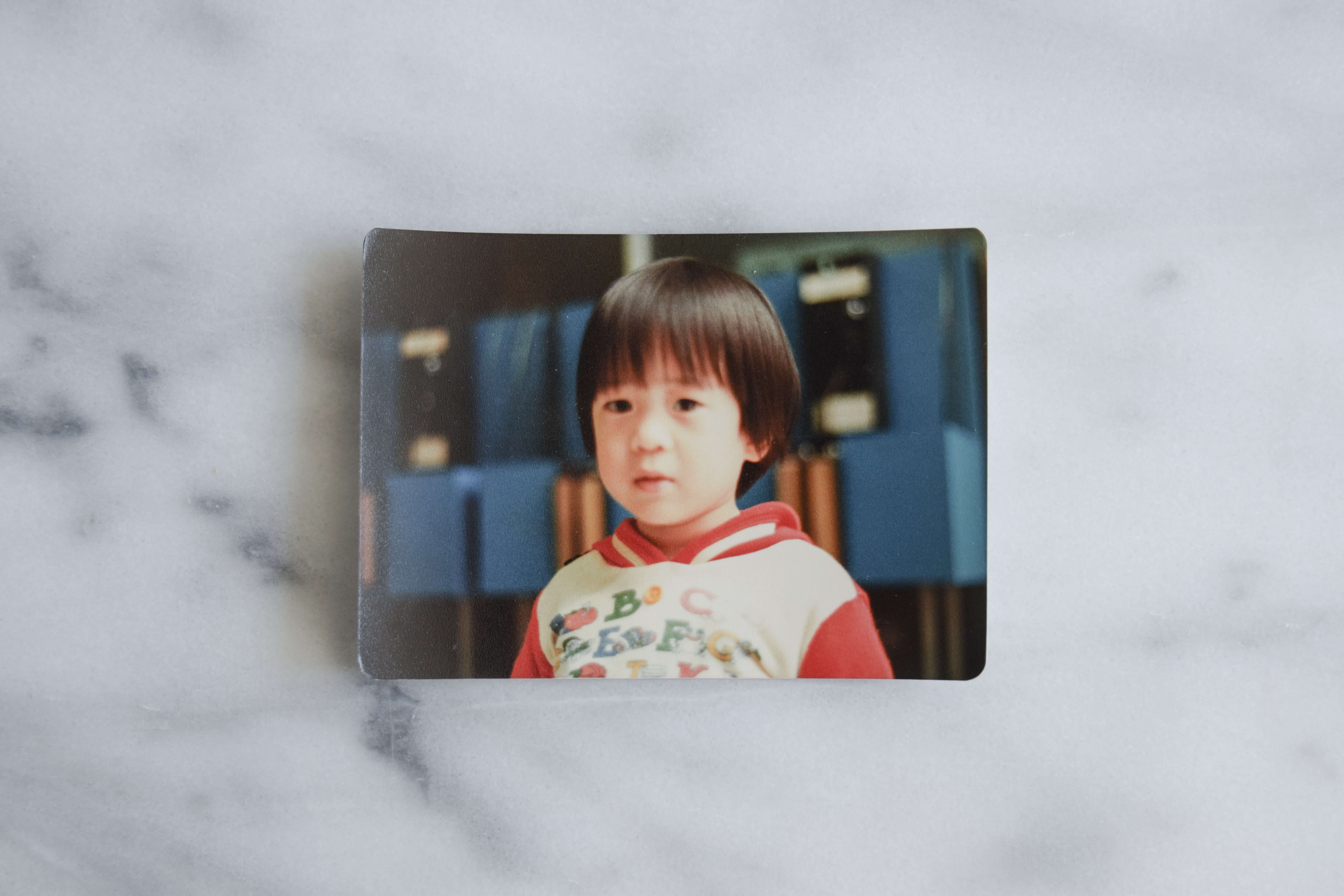

Lionel's disdain for school could likely have stemmed from his early experiences with the educational system. His childhood was transient and tumultuous. "Here it is," he tells me, when I press him for his narrative. "When I was four, my dad left. I don't remember anything before that. Me and my mom were struggling. She was always working and trying to provide, but she wasn't ready to be a single mom. She was super strict, like a lot of Chinese parents are, in a really non-nurturing way." Lionel lived in London, UK, Vancouver, and all over Toronto, which resulted in him attending six different elementary schools. "Who the fuck does that?" he asks, with exasperated rhetoric. "And kids are super mean. I got bullied, for sure. I would get the classic ethnic kid beatdown, and at some point you're just like, 'Why is this happening? What did I do?'"

Sometimes, Lionel would run away from home, and others he would simply get locked out. At nine years old, he was already preparing his own meals, as nobody else was available to cook for him. "You do all that for a few years," he describes, "And eventually you start to lose your fucking shit." One day, around age fifteen, Lionel decided he wanted some new clothes. "I wanted a jean jacket and a pair of jeans, and ain't nobody gonna go out there and get it for me. I gotta go and get it. I got a job at a telemarketing place. Worst fucking job ever." He lasted three weeks at the telemarketing position, during which time he secured his denim dream. "I realized, if I work, I can take care of myself. I don't need to deal with all the other bullshit. So, that was it."

"I don't know where the drive to hustle comes from," he tells me, "but I think part of it was that I always wanted to be better than my dad. If I am ever a father, I will be better than him."

Upon establishing that he could earn his own paychecks, Lionel moved away from his mother. He settled into a room at Bathurst and St. Clair, where he continued working and sustaining himself. "I don't know where the drive to hustle comes from," he tells me, "but I think part of it was that I always wanted to be better than my dad. If I am ever a father, I will be better than him."

He was diagnosed at twenty-nine, but it had been present in his body for two years. He had been suffering from all the symptoms, but had pushed them aside, attributing them to stress: "I lacked an appetite, I had insomnia, I was always suffering from some cold, and in one year I probably lost about 45lbs. I wasn't thinking. Work was crazy." One morning, he awoke to find a lump in his neck (which he has since tattooed to commemorate the 10 year anniversary of his remission). "I went to the doctor. I'd been going to him since childhood, I went to school with his kids and shit. I could see it in his eyes, he was like, 'Aw shit, something's wrong.' We did a bunch of tests and he told me there was a 98% chance it was either an aneurysm or cancer. He said that with an aneurysm, I could drop dead within two weeks. I broke down right then and there."??

"As much as you tell yourself not to get your fucking hopes up, you get your fucking hopes up."

Lionel began chemotherapy. "You have to make the decision, consciously, to do chemo. Nobody can make you do it. You either do it, or you die, and that's it." He underwent twelve cycles of chemo, one cycle being 2 weeks long. "It was the worst thing ever," he says. "After three cycles, I said fuck it, I'm good, I lived, let me go, I’m done. Chemo is poison. You're treating a disease with what is basically a worse disease. Your hair falls out, your skin turns green, your nails fall out, you want to puke all the time. I wouldn't wish it on my worst enemy."

He was furious at his predicament, which resounded at a religious level: "Me and Jesus, we ain't cool. My mom put me in a Catholic school, but I never really believed in that stuff, for many reasons. At that point, though, I was just mad and sad." Despite his coursing emotional spectrum and his physical illness, Lionel continued with chemo, largely due to the support and love of his cousin and a few of his boys. "That was the closest thing I had to family." ?

After several sessions of chemo, Lionel's oncologist suggested that he may only need to endure eight sessions in total. "Never tell someone that," Lionel says, emphatically. "As much as you tell yourself not to get your fucking hopes up, you get your fucking hopes up." After his eight sessions were completed, the tumor on his lung - previously the size of a grapefruit - was now the size of a golf ball. It was decided he must finish the full twelve sessions of chemotherapy before moving on to the radiation treatment. A year after treatment had begun, Lionel was declared to be in remission. " I was like a B celebrity in the cancer survival world," he grins. "I don't look the part, so the Canadian Cancer Society put me in a couple of TV spots and shit." He fondly recalls a segment on Breakfast Television, during which he was participating in a program called Extreme Survivors, sponsored by Extreme Fitness. "My trainer, who was basically a ninja, got me to do an exercise we'd never tried before because he wanted to look cool. He had me put one of my feet on a yoga ball and the other in the air, and underneath my hands I had another ball and a step, and I was balancing and trying to do push-ups... They were like, I can't interview this guy if he can’t talk! It was hard as fuck." ??

"Almost dying changes your perspective. You don't care afterwards, you're just happy to be alive, happy to be a human being, happy to travel, happy to hang with your homies. Why would I waste my time being fucking angry at what happened? It sounds cliché, but don't sweat the small stuff. Live life."

Lionel's second chance at life continued beyond television and exercise. "I traveled like a motherfucker!" he exclaims. "As soon as I was clear - because when you're full of radiation your body will set off alarms at the airport - I traveled to London and Paris. Now I go to Asia every year. In the last few years I've done Vietnam, Tokyo, the Philippines, and Hong Kong a couple of times. This year went to Singapore and Bali." He also found that his anger had dissipated a great deal. "Almost dying changes your perspective. You don't care afterwards, you're just happy to be alive, happy to be a human being, happy to travel, happy to hang with your homies. Why would I waste my time being fucking angry at what happened? It sounds cliché, but don't sweat the small stuff. Live life."

A few years ago he also started a clothing line, titled Bad Etiquette, which has since wrapped up its final fashion show. "For me, it was like a creative outlet. As a creative director, I don't actually get to create that much, so here was something that was mine. The name is kind of how I live my life - I'm not rude about it, I just actually never learned proper etiquette. For example, when I was nine, I had just come back from London and this kid shared his chips with me. That blew my mind. At nine, I was only just learning what sharing was." Bad Etiquette, though a healthy vessel for Lionel's energy and flow, proved to cost a great deal of time and money. "We had a fashion show last July, and we went out with a bang," he assures me. “I don’t regret it, and I would do it again.”

"One of my former bosses once said, 'Don't let us change you. You are here to change us.'"

Since the interview began, we've ordered at least three rounds of Irish whiskey. We've been talking for over an hour and our tongues are loosened. It's a perfect time to ask, "Has there ever been a time when your heart has led you astray?"??He immediately responds with, "I don't think so, man. I trust my gut and my heart. They've gotten me to where I am today. I make a lot of impulsive decisions. About eight years ago I sold most of my stuff, packed what was left in two suitcases, and moved to New York for a hot minute. I hustled like a motherfucker, but here I am. People always say you should save for your RRSPs and shit, but I don't even have savings.

You've got one shot at this. Don't fuck it up. I'm lucky, I got two shots, and now I'm just trying to have a good time and enjoy my life. ??We pay the bill and he leaves as abruptly as he came, as abruptly as he opened up to me. I am reminded of one of the first things he said to me: "One of my former bosses once said, 'Don't let us change you. You are here to change us.'" Despite all of his battles, Lionel's path and his conviction have left him unscathed by bitterness, which is one of the greatest challenges of all.