The modern day hero wouldn’t be caught wearing a cape, or fighting crime in an iron suit, or seen contemplating life from the tops of skyscrapers.

The modern day heroes are the people who inspire us to strive when the future is grim, to take another step when it seems impossible, to dance like no one is watching (when really, there’s always someone watching). The modern day hero inspires us by being their genuine selves.

As a regular civilian, I search for these kinds of extraordinary people; those that are inspirational in every day life. I yearn for them, I hunger for them: the heroes that save the day, on the daily.

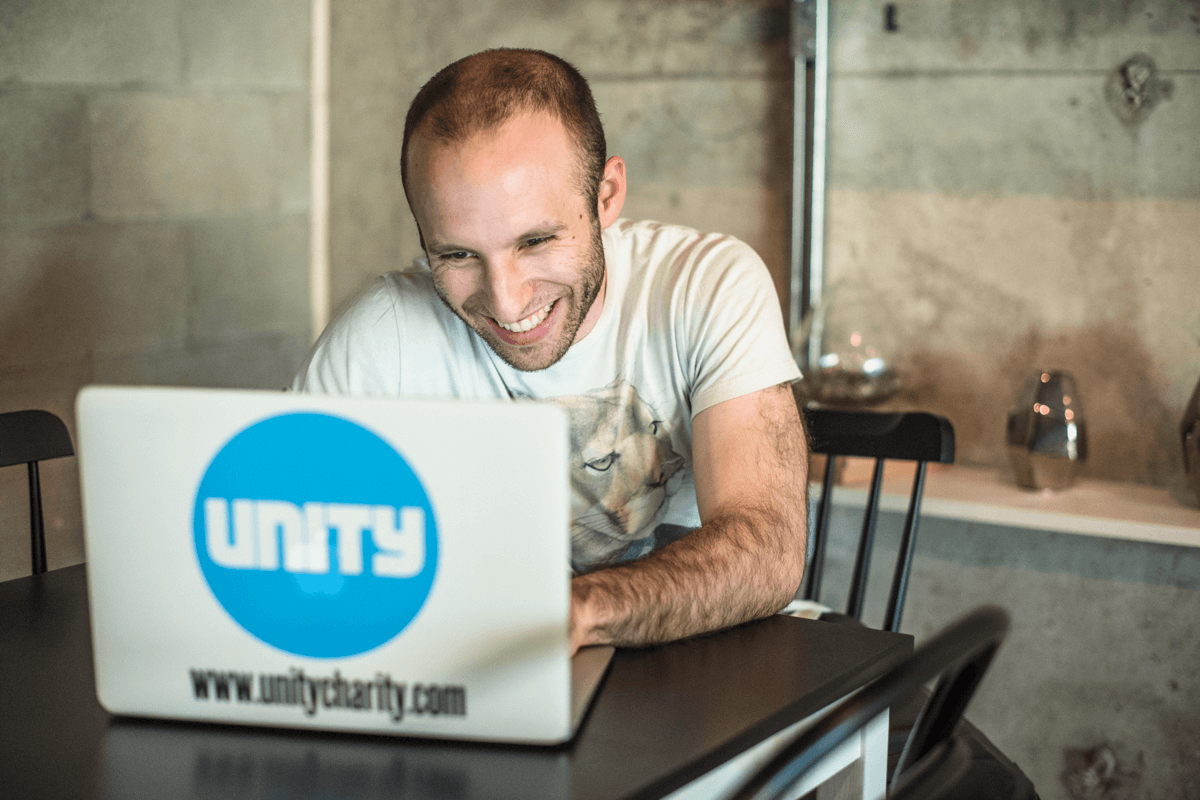

Mike Prosserman is nervous. He found a strange white insect on his shorts, and he's fiddling with his microphone while worriedly pondering whether or not the insect was a tick. It's surprising and endearing to see someone with such an impressive resume being so approachably disconcerted at the notion of a dainty bug. Mike is an extremely talented breakdancer, a successful entrepreneur and businessman, a role model, an activist, and one of the truest examples of empathy that I have yet to come across. "I'm freaking," he giggles, examining himself for the bug, "I'm bugging out, literally."

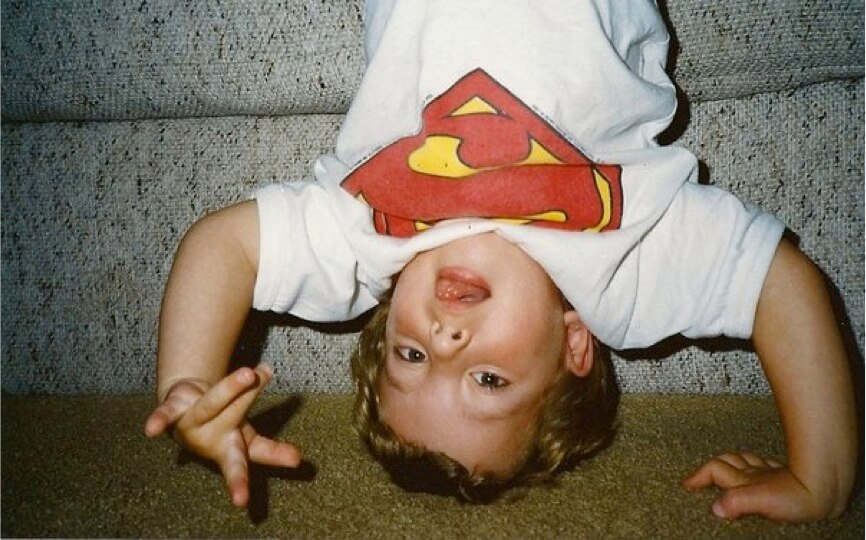

Mike's journey begins at the age of three - on his hands. "I was a very athletic kid. I would always walk around my house on my hands and drive my mom crazy with that... I would go up to the top of the stairs and she'd be freaking out, and then I'd go down to the bottom of the stairs and she'd be freaking out. I'd just do it for fun - like I'd make little games where I'd walk around and turn off light switches, or turn the TV off with my toes while I was upside-down." His mother, perhaps deciding if you can't beat them, you join them, enrolled him in gymnastics. Mike enjoyed the experience of flipping around in the gym until he attended a bar mitzvah in his neighbourhood of Thornhill at the age of twelve and was introduced to breakdancing. His father found him a breakdancing class with renowned Toronto b-boy Benzo, from Bag Of Trix, and Mike found himself attending classes at the former location for the Randolph Academy for the Performing Arts at age thirteen. He met his crew at these classes, and would participate in sessions with them at Danforth and Main, taking the subway from Thornhill. "I was totally out of my element," he says, "out of my world." As his newfound passion for dancing unfolded, his father and Benzo would sneak him into competitions at Comfort Zone in downtown Toronto. "Nah, he's good," Benzo would inform the bouncer at the door to the notorious after-hours. Mike's father was the only parent who was always present, and eventually became a surrogate father to many of the dancers, who referred to him as "Papa Piecez" or "B-Boy Daddy-o".

Eventually, Mike would break internationally, traveling with his father to LA and the UK to take part in competitions. In LA, Mike was involved in Freestyle Sessions 8, which took place on a boat after the venue was closed down. "People had travelled from all over the world, there were like 80 people from Japan there, and the police shut down the venue," he recalls, "People were going to riot - they wanted people to riot - but somehow the organizer got it on a boat." The UK competition was held in 2004, and Mike takes pride in "really representing Canada" with his international battles.

"My dad says when he grows up, he wants to be like me."

I am touched by how sincerely and earnestly he describes his parents' support throughout his early years and even in the present. "My dad would tag-team and be there as support. He's been a big influence on me following my passion. Same with my mom, but in totally different ways." When he was thirteen, his parents separated, and Mike would spend his time moving back and forth between his mother and father. "I just sort of felt the need to be that bridge for them, because they had done so much for me." I was impressed by the level of maturity he displayed at such a young age, and in response he modestly describes, "I feel like I was a very old person since I was young, always. I don't know where that came from, but I've always been very connected to people's emotions. I was an empathetic child, to the point where it would hurt me. I would hyperventilate when people were mad at me and I needed to carry a bag and just breathe." His parents continue to provide love and support to him, and are obviously proud of their son's accomplishments: "My dad says when he grows up, he wants to be like me."

*Photo provided by Mike Prosserman

Unity Charity itself began in Mike's eleventh grade entrepreneurship class, as the result of a project to write a business plan and run an event for charity. The event was called Hip Hop Away From Violence, with a logo modeled after the ubiquitous black and white Explicit Content sticker found on so many classic hip hop albums, and was held in the Thornlea Secondary cafeteria. One year later, Mike had become the president of student council, and "redirected resources" to grow his event. It was a huge success, with hundreds of attendees gathered in the gym to participate. Proceeds were donated to a charity called Leave Out Violence, or LOVE, which teaches photojournalism to youth in Rexdale and Lawrence Heights. Mike joined the board of directors of LOVE and began to take his event to neighbouring high schools, bringing his passion for hip hop as therapy to other youth in Toronto. After high school, Mike was accepted into Cirque du Soleil, but decided instead to pursue a business degree at York University. By his third or fourth year, he knew how to run a non-profit, thanks to his experience with LOVE, and he hired an articling student to register his event as a charity. After nine tedious months of awaiting a response, he was denied, leading to a bout of existential crisis and, consequently, a summer of travel. He advertised for a travel companion on Facebook and ended up in Asia for three months, one of which was spent teaching English in a mountain town called Yangshuo.

Unity workers use their personal stories and journeys to inspire and connect with their students, and they are expected to use vulnerability as a tool to break down walls and relate on a human level.

Upon his return to Toronto, Mike reapplied for charitable status and brought Malik Musleh, a grant writer, to his small team. Malik wrote a Laidlaw Foundation grant, which ended up bringing $40,000 to what would become Unity. Mike also placed as a finalist in the Top 20 Under 20 competition, which led him to a pitch competition at the finalist conference. His winning pitch brought in $5,000 from an insurance company called Freedom 55, which, combined with his Laidlaw Grant, allowed him to officially hire three people - himself, Malik, and a woman named Julla Shanghavi. Malik was given several months to write as many grants as he was able, which included Trillium, Ontario Arts Council, and Toronto Arts Council. Unity was awarded each of the grants they applied for, thus allowing Mike to raise his team's salary, pay his artists properly, and grow the organization even more.

"It's always weird. It continues to be uncomfortable, but it wouldn't be uncomfortable if it weren't real, so that's kind of why I feel it also works. This lays your cards out on the table and allows people to connect on a very human level."

When selecting artists to join his team, Mike asks some form of the question, "Have you ever thought about sharing your art with others?" He approaches performers and invites them to a Unity show, and has them participate in an artist training course to help them learn how to interact with the youth who attend the Unity program. Unity workers use their personal stories and journeys to inspire and connect with their students, and they are expected to use vulnerability as a tool to break down walls and relate on a human level. When I ask Mike if he finds it easy to be vulnerable, he explains, "It's always weird. It continues to be uncomfortable, but it wouldn't be uncomfortable if it weren't real, so that's kind of why I feel it also works. This lays your cards out on the table and allows people to connect on a very human level."

"My grandfather uses this analogy - it's like, you just got knocked out in a boxing ring, and the guy is like 8...9... And then you just get up, right before ten. That's always what's happening."

At the time of the interview, Mike has been running Unity for twelve years. During this time, he's faced an enormous spectrum of challenges, ranging from funding to procedural difficulties to personal interactions. "My grandfather uses this analogy - it's like, you just got knocked out in a boxing ring, and the guy is like 8...9... And then you just get up, right before ten. That's always what's happening." Some of the biggest challenges come from Mike's incredible capacity for empathy, occurring when someone needs to depart from the organization. Mike has had to learn to recognize when Unity is no longer helping someone, and he assists them in moving on in whatever way is best for their growth. He also has had to learn to let people go when they aren't an ideal fit for Unity, perhaps due to energy or mindset, and accepts responsibility for the situation. "Even though I know it's right for us and for the person, I still lose two nights of sleep or more when we have to let someone go or say something to someone they're not gonna want to hear. I've also learned when we don't do that, it's like this thing that lives under your skin and you're not being honest, so be honest, say it, even if it hurts your feelings or theirs. I'm saying that, but I'll still feel the physical anguish before I have that conversation."

Has there been a time when your heart led you astray?

As the interview draws to a close, I ask Mike the question that concludes each photostory: Has there been a time when your heart led you astray? He is unsure of how to answer, charmingly distracting me and trying to buy a few extra seconds of deliberation. Finally, he discloses, "One example is when I got into Cirque du Soleil, and decided, for some reason, it felt right to share something with other people versus do something selfishly. Another is when I traveled Asia and taught English for a month - I noticed a lot of people living in that city, and I was like, maybe I could live here, too, but I decided not to because it felt selfish. I would always go the alternative route of not doing the obvious self-fulfilling thing. I would do the thing that gave to others, which ultimately was more self-fulfilling than anything."

I leave my interview with Mike feeling calm, feeling secure, and feeling inspired. His blatant honesty and his endless wealth of humility is soothing. I think back to his earlier statement on vulnerability, and I realize his tactic has worked: In sharing his vulnerability and his story with me, he has allowed me to partake in one of the most honest and rewarding conversations I have been privy to. He approached me without barriers. I anticipate Mike finding fulfillment through hip hop, through teaching, and through giving for years to come.

Visit UNITY CHARITY for more information.

***Special thanks to PLENTEA- Parkdale location, for allowing us to shoot at their shop and also the tasty teas! With HEART.